Women in Chains

A new collection of Yiddish plays sheds light on the plight of the ‘agunes’

Inset image: Instagram

Inset image: Instagram

“In a significant sense, the modern Yiddish theater was born no sooner or later than when women were integrated on the Yiddish-language stage.” With this bold statement, historian (and Tablet associate editor) Alyssa Quint opens her introduction to a new collection of plays in translation, Three Yiddish Plays by Women: Female Jewish Perspectives, 1880-1920. These three plays, by three very different artists, are animated by issues that could not be more relevant today: reproductive autonomy and abortion, sex work, and the tragedy of the agune, or “chained woman.”

The women who wrote these plays themselves present a complex picture of artists at work. Lena Brown, author of Sonia Itelson or a Child … a Child, never saw her play produced or published. The manuscript sat in a drawer for decades, where it was discovered by her grandson in 2010. Quint suggests that, as a writer, Brown may have been able to tackle a subject like abortion so boldly precisely because she was writing “for the drawer.”

Maria Lerner, on the other hand, had the privilege of seeing her work on the stage and out in the world. She was half of an early Yiddish theater power couple, and she and her husband, the writer Osip Lerner, were colleagues of Avrom Goldfaden, the so-called father of modern Yiddish theater. That picture of a trailblazing, Yiddish-language artist couple becomes far more complicated, and more intriguing, when you learn that both Osip and Maria Lerner, as well as their children, converted to Christianity, while continuing to be closely involved in the Yiddish cultural world. Osip was even part of a team of Yiddish literati called in to work on a Yiddish-language edition of the New Testament.

As Quint tells us, women played important roles in the Yiddish theater as “theater managers, set designers, directors,” and of course, actors. The one area where women were drastically underrepresented was playwriting. In her introduction to Three Yiddish Plays, Quint notes that women writers in the Yiddish literary scene were up against formidable institutional and interpersonal obstacles. Indeed, while women held many positions of power in the theater, their output as writers represented a tiny fraction of the work done by men. That alone makes these three plays notable.

Also notable is the fact that all three plays feature female protagonists, characters who can be read as “alter egos to the educated middle-class playwrights who created them.” More alarming is that all three female protagonists die in the final act. And while it’s true that the conventions of tragedy and melodrama no doubt favored such heavy-handed resolutions, they were not inevitable.

Almost at the exact same time that Maria Lerner’s Rosale first died of shame at the close of The Chained Wife (1880), Henrik Ibsen’s Nora was herself rejecting suicide in A Doll’s House (which premiered in December 1879), courageously shutting the door in an exit heard round the world. While the playwrights of Three Yiddish Plays were able, to some extent, to assert themselves as individuals and artists in the wider world, it seems that, unlike Ibsen, they could not imagine a different ending for their characters, and a different world for themselves.

The Chained Wife (here ably translated by Elya Piazza) is the earliest known Yiddish play by a woman and was one of the first Yiddish productions to be staged that was not driven by music. The play offered what Quint calls “prosaic suffering.” The people on stage look a lot like those in the audience, and their problems are those of fairly ordinary, upwardly mobile Jews of the Russian Empire.

Our protagonist, Rosa, is the sheltered daughter of wealthy parents, Mr. and Mrs. Grossman. She is in love with the earnest and kind Adolf, an employee in her father’s business. Rosa and Adolf want to marry, but Mr. Grossman has set his sights on a business associate, Neumann, for his soon-to-be son-in-law. After all, how could his daughter be expected to marry a mere employee? Eventually, the lovers are separated, Rosa is worn down by her father’s insistence, and she accepts Neumann as a groom.

Things go sour quickly for the newlyweds. Neumann is revealed to be a gambler and a spendthrift, a lowlife cad eager to spend Rosa’s money. He then abandons her without a divorce, leaving her a “chained wife,” or agune, under Jewish law. In order for Rosa to go back and marry her true love, Adolf, they must send an associate to find and procure Neumann’s signature on a writ of divorce, or get. Once completed, the couple enjoy an offstage happy ever after of approximately 19 years. That 19-year interlude is important, because it’s the minimum amount of time the young newlyweds need to advance to the wedding of their own daughter, Adele.

The final act opens on Adele’s wedding day. Alas, the dastardly Neumann bursts in like a late imperial Kool-Aid man, back from Siberian exile to announce (truthfully) that his signature had been forged on the divorce document. Neumann’s attempt at blackmail, and the revelation that Rosa’s children will now be considered mamzerim (bastards) under Jewish law, brings her to a tastefully bloodless onstage death.

Though the play had multiple productions and was quite successful, not everyone was a fan. The great historian and cultural figure Simon Dubnow reviewed an 1889 production. Quint quotes him thusly in her introduction: “With predictable tropes such as swindlers, murderers and an innocent victim …” the play is “full of sentimental and ornamental language.” And he’s not wrong.

Rosa is a perfect victim. She is a victim of her father’s insistence on money over love when choosing her groom. She is also a victim of Neumann, the mustache-twirling bad guy who pawns her jewelry and uses her desperation for a get to blackmail her. When Neumann’s signature is forged on the document, Rosa is at home, suffering innocently, hundreds of miles away. And that’s the problem. In A Doll’s House, Nora is the one who forges her husband’s signature, setting the play’s events in motion. Nora may be a victim of a society that infantilizes women, but unlike our darling Rosale, she isn’t perfect, and that’s precisely what has made her, and the play, so enduringly compelling.

But that doesn’t mean that The Chained Wife isn’t interesting. With the trope of the get gone wrong, its outlandish circumstances, and the ensuing melodramatic misery, Quint suggests that Lerner was less interested in the tragic reality of abandoned wives, and more interested in making her own argument for women’s rights. Such a strategy allowed her, and other writers who used the get as a melodramatic trope, “to avoid the more knotty and relevant issues that beset women of their age—issues, for instance, having to do with motherhood and reproductive health—as they might conflict with the bourgeois aspirations of the rising Jewish middle class.”

I agree with Quint that Maria Lerner may have gravitated toward the get as a dramatic trope so as to avoid dealing with the contradictions between her class aspirations and the gendered limitations that went along with bourgeois upward mobility. Her Rosa gets to be both the perfect Jewish daughter as well as the perfect victim arguing for women’s equality, without sacrificing any of her likability. But I think there’s something else right below the surface of the text, popping into view at a few key moments. Quint says that an attraction to Christianity is evident in Osip’s Yiddish plays, but not Maria’s. And here I strongly disagree.

The Grossmans are portrayed in a kind of cultural limbo. They are obviously Jewish and still beholden to Jewish law, as tragically demonstrated with regards to the need for a get. And yet … The family’s life and fortunes revolve around business, not the Jewish community. Rosa articulates this quite clearly when contemplating her own daughter’s match: “… nowadays, Jews have changed what they mean when they talk about ‘lineage’ [yikhes]. Good lineage used to mean he descended from a great rabbi, a judge or a great student of Torah, or an honest merchant. Recently, though, lineage means money.” As Rosa’s story has shown, that new understanding of “lineage” brings nothing but misery. But rather than returning to the old values of yikhes, Rosa has learned to replace them with her own worldly judgment: “No one looks at honesty anymore, but I’m glad that our Adele is going to marry someone we know personally and that we also know the house he comes from.”

In the third act, while contemplating the need to hunt down Neumann and obtain his signature for the get, Adolf and Rosa have a long, philosophical dialogue about what their relationship can be, suspended as it is between the state of passionate friendship and married couple, and seemingly at the mercy of unseen rabbis and their callous laws. Rosa envisions their love entering a third phase, beyond romantic love, where Rosa and Adolf will now be like brother and sister. Is this perhaps an echo of the promise of becoming brothers and sisters in Christ?

To this odd fantasy, Adolf counters: “I would only feel so good if I knew there were some kind of sacrifice I could offer that would free us once and for all from this law that binds our Jewish daughters.” A law, he notes, which does nothing to protect women from the whims of very bad men. “Oh, how strict these laws are. We must abandon them!” Yes, Adolf is quite explicitly arguing for equality between men and women, but the manner in which he and Rosa are dialoguing seems to me deliberately threaded with subtle allusions to a possible future, one in which the cruel legalisms of Jewish life have been superseded. The rabbis, Adolf says, are “so attached to every single letter that they can’t allow a single reform.”

Finally, the climax of the play features a stand-off between the wicked, blackmailing Neumann and the absurdly useless rabbi, the same one who officiated at Rosa and Neumann’s long-ago wedding. He has returned to marry off Rosa’s daughter Adele. Neumann brings him the proof that he and Rosa are indeed still legally married and he insists that the rabbi publicly rule on the validity of the marriage. As written by Lerner, the rabbi is almost more contemptible than Neumann, flailing helplessly in his acquiescence to what the facts, and the law, supposedly demand. “Of course,” the rabbi says, “we cannot go against the law. We must uphold our laws. Even when people are very decent, honest. Even when they aren’t guilty. Probably God willed it this way …”

But the rabbi is really only there as a foil. He provides Rosa with the opportunity to make her most important speech, in which she denounces his eagerness to rule her children unfit for proper marriage matches. Turning to her husband Adolf, Rosa explodes in a righteous anger: “This is how your laws are. According to your law, there are bastards, but not according to holy nature! She does not discriminate! All are equal to her!”

It’s likely that A Chained Wife was written before Maria and Osip Lerner’s official conversion. Even so, it’s hard to read Rosa’s death speech today and not hear its resonances with the liberatory promise of Jesus Christ, especially as articulated in the Book of Galatians: “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus. And if you are Christ’s, then you are Abraham’s offspring, heirs according to promise.”

Did Maria Lerner really believe that in order to empower Jewish women and to reform Jewish life, it had to be superseded by the church? It’s difficult to say, given the archival evidence we have today. And as we see in the play, Rosa’s only option, at least on the stage, is death, not conversion. Rosa does not go quietly, but allows herself to be martyred to an unjust Jewish law, night after night, for the entertainment of an audience of modernizing Russian Jews, some of whom no doubt identified with Rosa’s predicament.

Over a century later, the scandal of agunes still plagues many Jewish communities. What’s so interesting, and even hopeful, is that women in those communities are creating change around agunes, fearlessly taking up the discursive tools at their disposal. In her recent book about ultra-Orthodox female artists and influencers, For Women and Girls, scholar Jessica Roda describes how some of these women use their visibility to push for justice for agunes. There is “an emerging online community of frum female artists and celebrities who mobilize social media to advocate for women’s empowerment and structural changes within Orthodoxy. Through this process, they create a counterpublic space to the public ultra-Orthodox media—a space where they are not overseen by religious authority.”

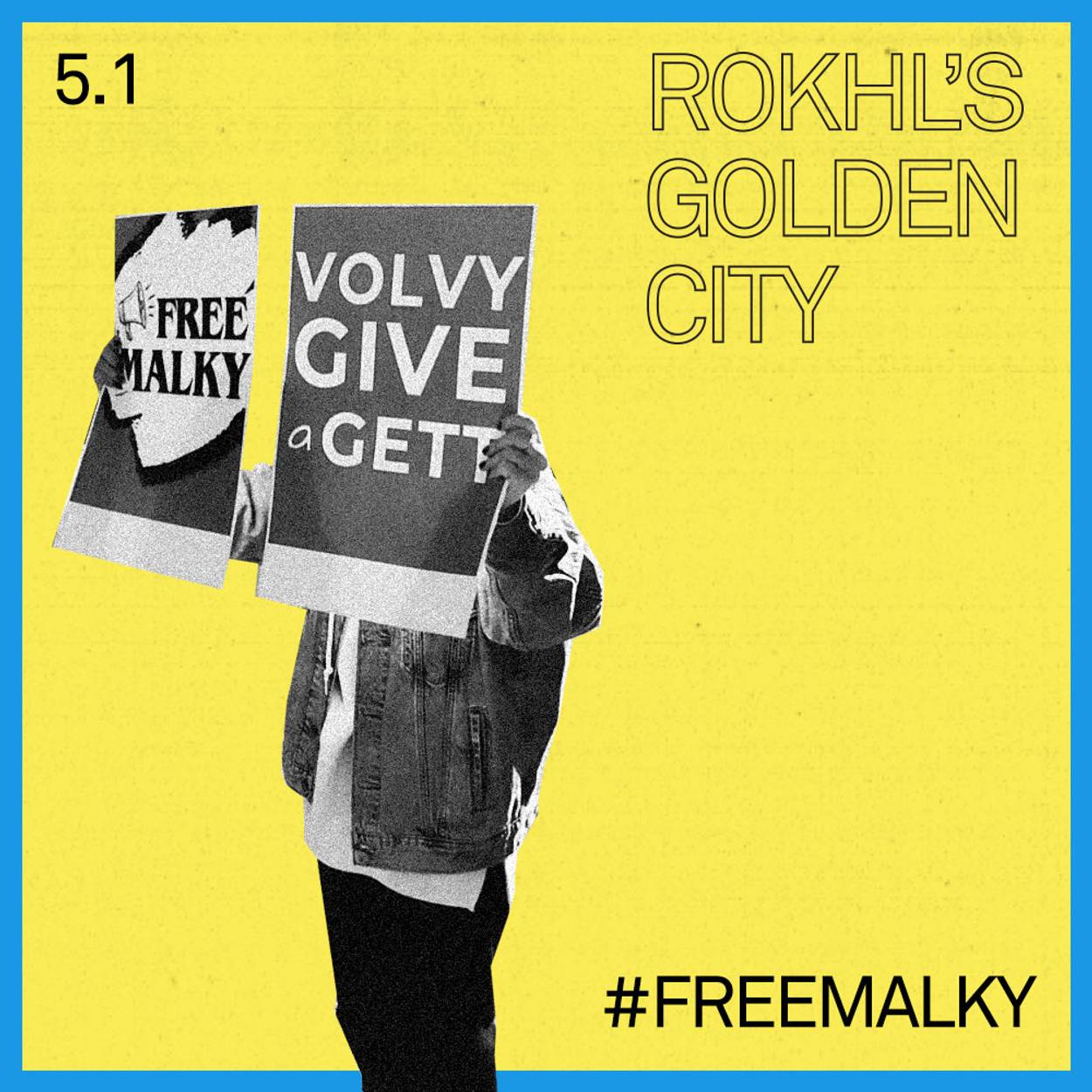

Best known of these is FlatbushGirl, Adina Sash. Sash has a genius talent for using Instagram and social media. Her advocacy for an agune named Malky Berkowitz is its own kind of modern Yiddish theater, transforming one woman’s experience into an ongoing drama (#FreeMalky), complete with mustache-twirling villains and righteous heroes. As Roda describes it, doing this work requires a deft negotiation of competing values. Frum female “celebrities” can only exist if they are seen and heard, but they are doing so within the context of communities whose core values prioritize the absence of women’s voices and faces from the communal stage. It’s a real-life drama as compelling as anything Maria Lerner might have invented for the Yiddish stage, and one whose stakes remain just as high.

READ: Three Yiddish Plays by Women: Female Jewish Perspectives, 1880-1920 (2023) … Women on the Yiddish Stage (2023) … The Rise of the Modern Yiddish Theater (2019).

ALSO: Coming up at the Bang on a Can Long Play Festival, two performances of The Great Dictionary of the Yiddish Language, a new opera about the greatest Yiddish dictionary that never got past “Alef.” May 4, 2 and 5 p.m. More information here … Coming to Joe’s Pub: Kleztronica: Chaia & Eleonore Weill “bring a duo repertoire inspired by a long tradition of radical female mentors. Join us for a night of Yiddish song, electronic grooves, klezmer tunes, and space hurdy-gurdy.” May 4 at 9 p.m. Tickets here … Once again, the Queens Public Library (Kew Gardens Hills) has a wonderful slate of Yiddish-related programming for Jewish Heritage Month. Sundays, May 5, 12, and 19. See full details here … My brilliant friend, klezmer fiddler Ilana Cravitz, can now be heard on the BBC talking about the history of klezmer music. Listen here … Hey! KlezKanada will be at an all-new campsite this year, with the same stellar faculty and classes as always. I’m happy to say I will be returning to the KlezKanada faculty after being away for a number of years. I’ll be teaching a writing workshop, lecturing on “Everyday Ashkenazi Magic,” and more. Scholarship applications due by May 1! Check out the full program and get yourself registered. KlezKanada Retreat: Aug. 20-26, 2024.

Rokhl Kafrissen is a New York-based cultural critic and playwright.